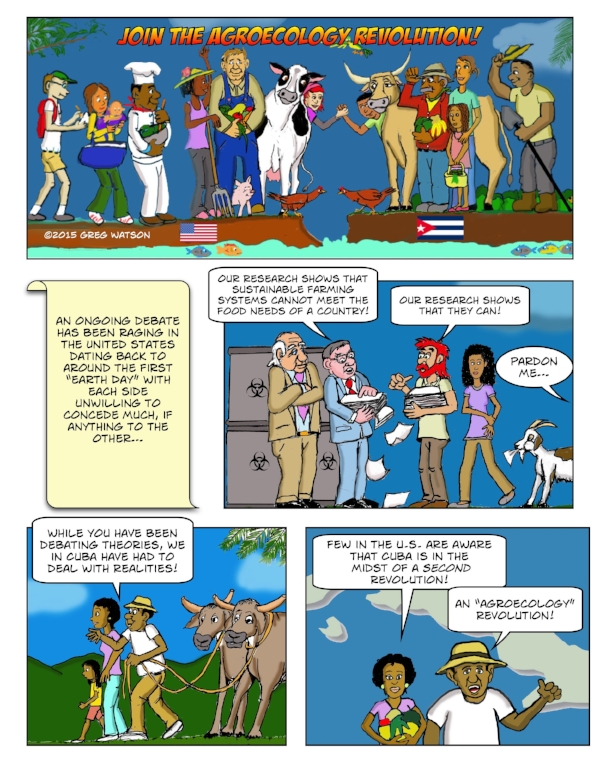

I wrote this essay for the New Alchemy Quarterly in 1983. The photo shows Bucky in the New Alchemy "pillow dome" with Nancy Todd, Liz Fial, J. Baldwin and John Todd. - GW

R. Buckminster Fuller’s insights inspired the creation of the Whole Earth Catalog. He is responsible for introducing concepts such as “whole systems", "comprehensive anticipatory design” and "synergy" into our vocabulary. More than 300,000 of his geodesic domes dot the globe, serving functions ranging from housings for radar equipment to year-round passive solar greenhouses. He has written more than 25 books, and by his own account has traveled more than 1,200,000 miles - or the equivalent of 48 trips around the planet - delivering lectures and consulting with heads of state, architects, designers, artists, schoolteachers and community activists.

Despite all this, Bucky, as he preferred to be called, was still a figure more admired (or in some cases dismissed or scoffed at) than understood. In this, he was not unlike other great thinkers. Most of his profound insights and discoveries have been obscured in the limelight of his more dramatic and tangible inventions like the dome, the Dymaxion House and the Dymaxion Car. However, if there is any truth in the saying regarding hindsight's near perfect vision, I'm certain that future generations will acknowledge Bucky as the discoverer of no less than the mathematical principles by which the universe expands, snowflakes form, florets distribute themselves in pine cones, DNA twists, thoughts take shape, and gravity manifests itself as love, all of which disclosed themselves to him upon his discovery of what he calls “Nature's Coordinate System."

Bucky's discovery of Nature's way of doing things was the result of a 56-year commitment he made to himself: "Dare to speak and live and love the Truth." Bucky’s passionate pursuit of the eternal verities of Universe were motivated by feelings similar to those expressed by renowned biologist C.H. Waddington shortly before his death:

"Most people are beginning to feel that they must be thinking in some wrong way about how the world works... the ways of looking at things that we in the past have come to accept as common sense do not work under all circumstances, and it is very likely that we are reaching a period of history when they do not match the type of processes which are going on in the world at large."

Bucky was not at all reluctant about pointing out exactly where he thought our thinking went askew:

"Science's mathematical language is not based on experimental evidence. Science refers all events only to its three-dimensional x,y,z coordinates. Physics has found no straight lines - has found only waves. Physics has found no solids - only high frequency event fields... Universe is not conforming to a three-dimensional perpendicular-parallel frame of reference. The Universe of physical energy is always divergently expanding (radiantly) or convergently contracting (gravitationally).”

What Bucky was telling us is that Nature is not logical. That's not to say that nature is beyond reason. Gregory Bateson, ecologist/anthropologist who loved to delve into matters of epistemology, once wrote: "Logic is a poor model for cause and effect." Bucky simply presented us with a more accurate model: Synergetics. "Synergy alone explains the eternally regenerative integrity of Universe. You cannot understand nature if you do not understand synergy.”

Synergy is a fundamental principle of whole systems and therefore of ecology. It refers to "the unique behavior of whole systems unpredicted by the behavior of their respective subsystems' events." A corollary of this synergetic principle is: You can't predict the whole by looking at its parts in isolation. Bucky's discovery of synergy uncovered the flaws in reductionist science, the way that most of us have been taught to think about the world and the manner in which we approach problems.

"Evolution," said Bucky, "is bound and determined to make humanity a success.” The fact that we seem to be headed deeper and deeper into one crisis after another might seem to contradict that claim. But Bucky was convinced that collectively humanity now possesses the know-how and resources to take care of all humanity for generations to come and to do so at higher standards of living and individual freedom than any humans have thus far experienced or even dreamed of, while in no way endangering the ecological integrity of our planet.

If we are only willing to observe Universe and talk about those observations without falsifying them, we can learn how the harmonious all-embracing set of relationships we call ecology allows nature to achieve maximum results with minimum use of materials and energy. Our ability to discover and apply Nature's eternal principles to problems of human design is the key to the salvation of our planet for Bucky. Real wealth is know-how -- the ability to do more with less.

“The world teeters on the threshold of revolution. If it is a bloody revolution it is all over. The alternative is a design science revolution. Design science produces so much performance per unit of resource invested as to take care of all human needs. This can be accomplished by each individual's acquiring working knowledge of Nature’s coordinate system.”

So, Who Was Bucky Fuller? by Greg Watson

To learn more about Bucky and his work, visit the Buckminster Fuller Institute website.